Bob Metzler: Thinking Globally and Acting Locally for Public Education

For nearly 100 years, Robert Metzler (BA ’52, MA ’55) has been experiencing, practicing and preaching the benefits of “personalized learning.” Now, with a planned gift of $2 million from his estate and $750,000 from his sister’s estate, he has established the Metzler Family Scholarship Fund—the largest in the history of the Morgridge School of Education—to ease the financial pressure for generations of teachers and school leaders who believe as he does.

Matching funds from DU’s Momentum Scholarship program ensured that Metzler’s scholarships could be awarded immediately, and that he could meet some of the people who are shaping the future of public education, and of DU itself.

Metzler’s first teaching job was in a one-room school—long before teachers were required to earn four-year degrees and pass certifications. He saw how much impact a well-trained teacher could have on individual learners. He saw the folly in forcing synchronous learning.

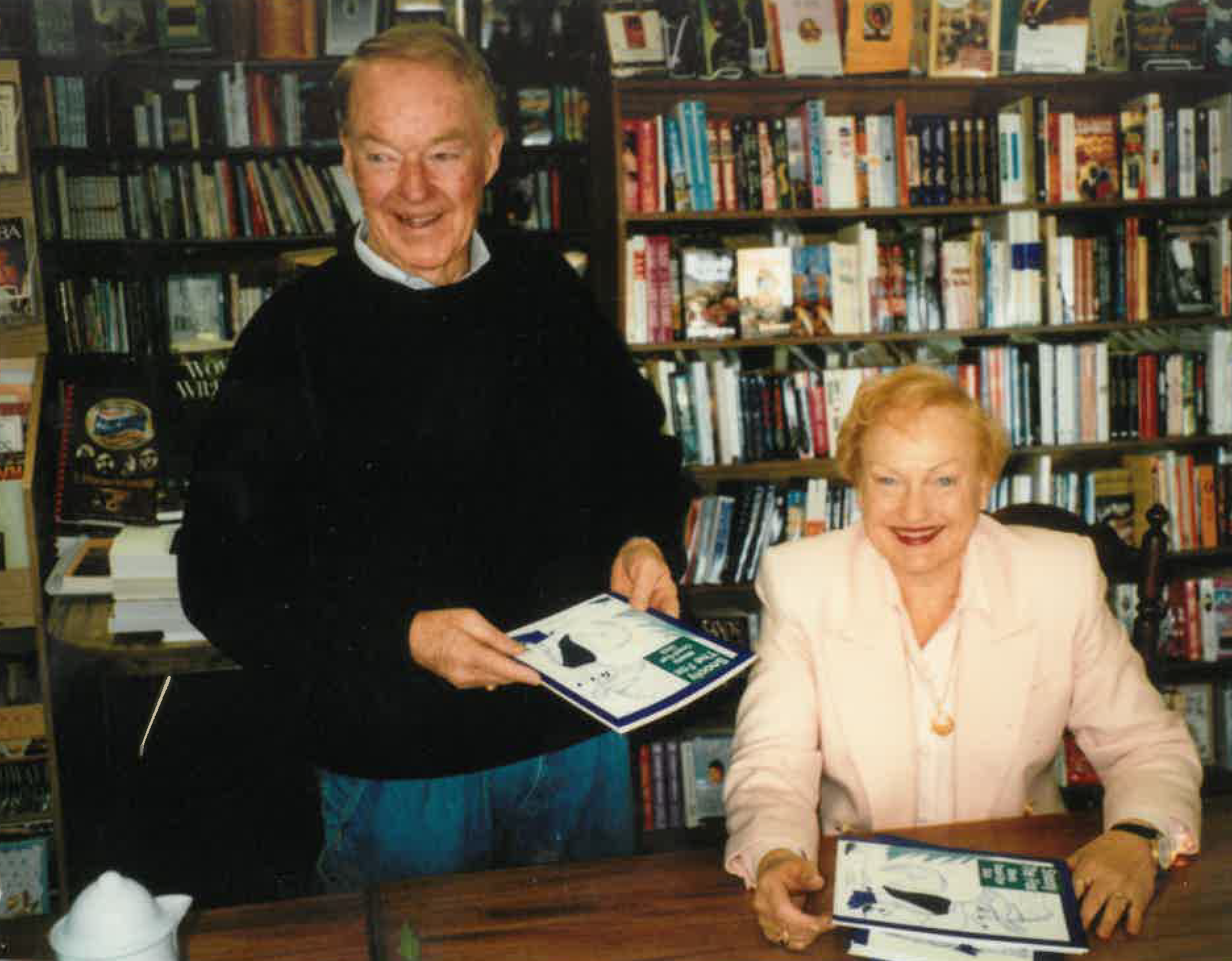

Bob and Rosemary Metzler

“Not everybody in a fourth-grade classroom was at the same stage,” he said, “and yet, they were all learning about Columbus discovering America. So we formed teaching teams, to focus by subject matter.”

By 1963, Metzler, a fifth-generation Coloradan, was at a career crossroads. He had been a student teacher during high school and, thanks to financial aid, earned his undergraduate degree at DU. He also had served as a school principal and as the elected superintendent for Douglas County schools. All the while, he was responsible for the cattle on his family’s ranches near Castle Rock.

“I thought if I was going to advance in the field of education, I would need to go out and see other districts and gain experience,” he said. And yet, he turned down a prestigious leadership post in California, choosing instead to serve his home state as superintendent of schools for Clear Creek County, a position he held until 1974.

“Public schools were being highly critiqued nationally as not meeting the needs of the country, and the Clear Creek Board of Education wanted more innovation and improvement of its schools. I decided that if I could build from scratch the ideas I liked, in rural Colorado, that would be more impactful to the field of education than going somewhere that was already more advanced.”

So Metzler relocated to Idaho Springs, just 60 miles northwest of Castle Rock. He organized a citizens committee, talked to the communities and held a public vote. Before long, the community had a very different kind of high school. “It had flexible setups. Students worked in teams that suited their learning styles and abilities. And we recorded the lectures, so students could listen in a lab more than once, to assimilate what they learned.”

“Neither my sister nor I ever married, so we knew we had investments that wouldn’t be passed on. Because of our experience at DU, we decided we wanted to give scholarships that will be perpetual.”

Metzler’s work attracted attention from the Ford Foundation. “We gave tours of the building and shared our program with people from foreign countries who came to see what we were doing.” Metzler served on the National Board for Rural Education. With a team from Columbia University, he shared his ideas at the 1964 World’s Fair in the pavilion sponsored by AT&T.

“We were living proof,” he said. “If it could be done here, it could be done elsewhere in the world.”

Following his work in Clear Creek, Metzler joined the administration of Colorado Mountain College, where he developed new concepts for lifelong learning and distant delivery of learning opportunity for students in rural Colorado. After eight years there, he continued his professional career internationally.

Today, Metzler is the last living member of his family. His sister, Rosemary (BA ’60, MA ’70), who passed away in 2017, also was a Pioneer. She spent a year teaching at the American School in Izmir, Turkey, and a summer in Sierra Leone. She taught English for 33 years in Douglas County, specializing in Shakespeare and British Literature, and she later authored a series of popular children’s books. She lectured at DU.

“Neither my sister nor I ever married, so we knew we had investments that wouldn’t be passed on,” he said. “Because of our experience at DU, we decided we wanted to give scholarships that will be perpetual.”

Metzler recently met the first two recipients of the scholarship, both of whom have lived and worked in rural locations in the United States and abroad. Lily Werthan (MA ’18) recently completed a master’s degree in Curriculum and Instruction in Secondary English, with a focus in culturally and linguistically diverse education. In the fall, she will begin working as a seventh-grade reading teacher with DSST Public Schools. She said she aims to “help transform the education system, both to better serve students from diverse backgrounds and to bring more joy, passion and purpose into formal education.” Andrew Fox is on track to complete a PhD in Education Leadership and Policy Studies in 2020.

Growing up, Fox could see DU from his bedroom window, but he never imagined attending. “It was physically close, but light years away in terms of attainability.”

“I was really impressed with both of them,” Metzler said. “In a lot of ways, they represented what I had done.”

Fox, a first-generation college student, recalled their first meeting: “I think it was the meeting of two souls. His whole life, Mr. Metzler has adhered to the principle ‘Think globally, act locally.’ He knows that while we all have a common purpose and need a common base of our citizenship—reading, writing, arithmetic, critical thinking—to get to that goal, we need more compassion for individual differences.”Fox, now 29, lived in Ghana, West Africa, while earning his master’s degree in Public Health from Drexel University in Philadelphia. For the nonprofit A Better Chance, he worked for a year as a live-in tutor to eight academically gifted boys from rough neighborhoods in Washington, D.C, and New York. And for one year between undergraduate and graduate school, he worked for City Year Philadelphia.

Fox saw up close that “looking only at test results or grades ignores the cosmos of a student’s whole life.” As a school leader, he aims to combine health with public education.

Growing up, Fox could see DU from his bedroom window, but he never imagined attending. “It was physically close, but light years away in terms of attainability,” he said, “so I’d go over on my skateboard. I’d say to myself, ‘I’ll never be part of this system, so I’ll grind on your concrete.’ But I matured, applied and was accepted.

“If not for the Metzler scholarship, I wouldn’t be here,” Fox said. “What Mr. Metzler is doing will ripple out for generations and generations. It has already rippled out to me.”